Common Neoplasms

- related: Dermatology

- tags: #dermatology

Benign Neoplasms

Seborrheic Keratosis

Seborrheic keratoses are benign pigmented neoplasms of keratinocyte origin that are common in adults. They are “stuck-on” papules and plaques that occur anywhere on the body but are most common on the trunk and spare the palms, soles, and mucous membranes. Seborrheic keratoses range in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. Usually they are brown, but they can range in color from tan to black (Figure 64). They can mimic melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma, but skin biopsy confirms the diagnosis. They may become irritated or excoriated. When seborrheic keratoses are symptomatic, they may be treated with cryotherapy or shave removal.

Melanocytic Nevi

Melanocytic nevi are benign neoplasms composed of melanocytes commonly referred to as “moles.” They occur anywhere on the body including palms, soles, and mucous membranes. Melanocytic nevi can appear early in childhood and increase in number until middle age. They vary in clinical appearance depending on the location of melanocytes within the skin (Table 16 and Figure 65). Clinically they can mimic melanoma, necessitating a biopsy for accurate diagnosis.

Dysplastic Nevi

Dysplastic nevi are melanocytic nevi that are often asymmetric, irregularly bordered, have more than one shade of brown, and may be quite large in diameter. Many have a “fried egg” appearance with an eccentric dark brown papular center and surrounding light brown ring. Dysplastic nevi can display one or more of the identifying characteristics of melanoma (see Malignant Melanoma), making an accurate clinical diagnosis impossible. In cases of uncertainty, a biopsy of the lesion can typically exclude melanoma; however, it is imperative to sample the entire lesion including a 1- to 2-mm border of normal surrounding skin.

Although melanoma can arise within any melanocytic nevi, including dysplastic nevi, the risk of this occurring within any given lesion is quite small. Removal is reserved for those lesions that display particularly worrisome features, are changing in size and color, are symptomatic, or stand out from the patient's other nevi. Patients with multiple dysplastic nevi are at risk for developing melanoma and should be monitored closely (Figure 66). Some of these patients have dysplastic nevus syndrome. Criteria for this syndrome include a history of melanoma in one or more first- or second-degree relatives, the presence of a large number of nevi (>50), multiple nevi having atypical clinical features, and multiple nevi that have atypical histologic features. These patients are at increased risk of melanoma and should have yearly full-skin examinations.

Halo Nevi

Halo nevi are benign melanocytic nevi that are in the process of being attacked and eliminated by the immune system.

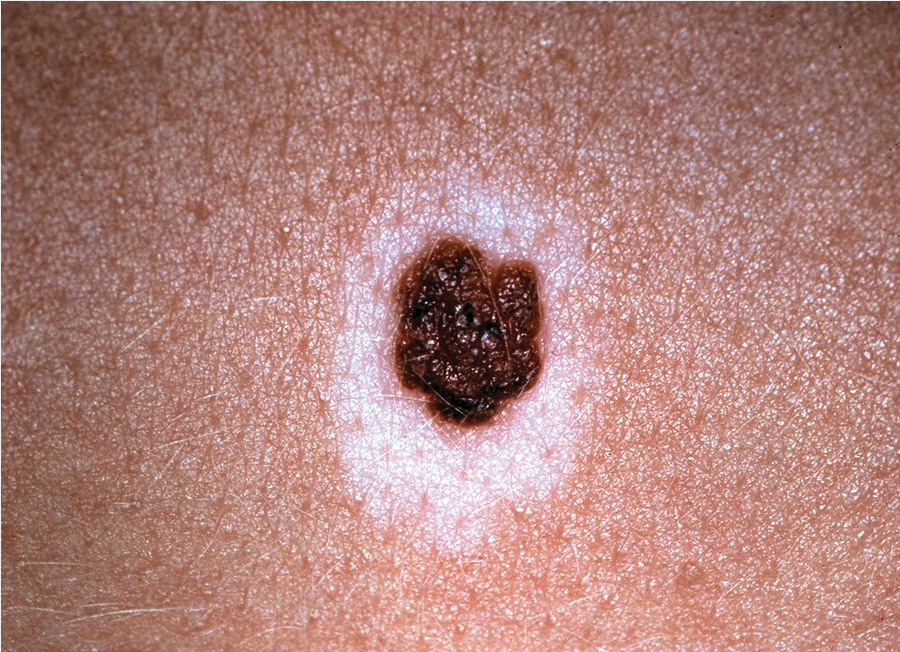

Halo nevi are melanocytic nevi with an admixed chronic lymphocytic infiltrate that signifies regression of the nevus. Halo nevi are central brown-to-tan macules or papules with a surrounding “halo” of hypopigmented or depigmented skin (Figure 67). They most frequently present on the back of teenagers or young adults. Multiple halo nevi have been associated with melanoma; therefore, these patients should have a complete skin examination.

Sebaceous Hyperplasia

Sebaceous hyperplasia is a common benign condition consisting of flesh-colored or yellow umbilicated papules found on the face of older patients, particularly the forehead (Figure 68). The lesions are often multiple and are more common in patients with rosacea. Histologically, there is enlargement of the sebaceous glands surrounding a hair follicle. Sebaceous hyperplasia can mimic basal cell carcinoma and may necessitate a biopsy for accurate diagnosis.

Callus/Corns

A callus is a collection of thickened, hardened stratum corneum that presents as a flat papule or plaque at the site of repetitive trauma, frequently under bones. Sometimes the term “corn” is used interchangeably with callus; however, corns have more distinct edges, are more rounded, and have a central core that can be soft or hard. Corns are typically seen on the sides or tops of toes. Treatment is by mechanical or chemical paring with salicylic acid, but removing the pressure from the site is necessary to prevent reformation.

Acrochordon (Skin Tags)

Acrochordons (skin tags) are skin colored, pedunculated papules (Figure 69). They are most commonly seen on the neck and skin folds in older adults. Skin tags appear with increased frequency during the second trimester of pregnancy and may regress postpartum. Skin tags are frequently seen in patients with obesity and in patients with diabetes mellitus. Perianal skin tags are common in patients with Crohn disease. If lesions become necrotic or crusted, they may require removal with cryotherapy or snip excision. They can be of cosmetic concern, especially when numerous. The presence of numerous lesions, particularly in the setting of obesity and acanthosis nigricans, is associated with insulin resistance.

Cherry Angiomas

Cherry angiomas are benign vascular lesions with a familial predisposition that present in adulthood and become more numerous with age. They are discrete red-to-violaceous papules that blanch with pressure, more common on the trunk but can be seen anywhere on the skin (Figure 70). Shave removal or electrocautery may be required for lesions that are traumatized or bleeding.

Dermatofibroma

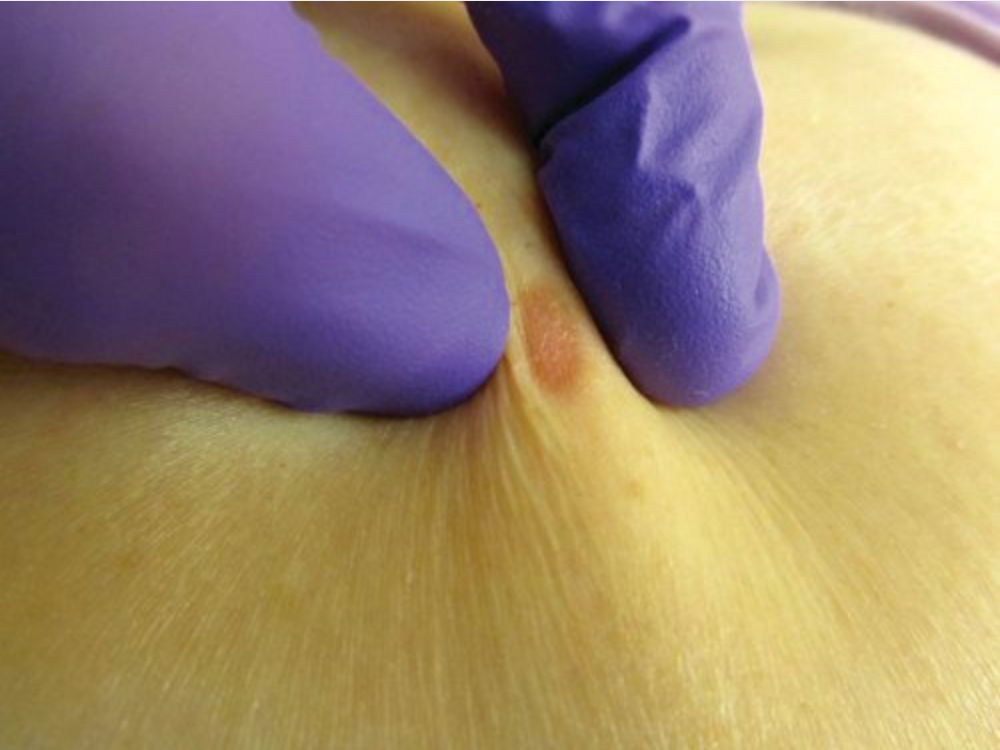

Dermatofibromas are benign, fibrohistiocytic lesions that are common on the extremities, particularly the legs of young women, and are associated with trauma. Dermatofibromas are tan-to-brown discrete papules that often have a slightly darker brown ring encircling the main part of the lesion; they “dimple” when lateral pressure is applied to the lesion with the thumb and first finger (Figure 71). Treatment is not necessary, and recurrences are common after shave removal. Multiple dermatofibromas have been associated with HIV infection and systemic lupus erythematosus.

The “dimple sign” is a characteristic clinical feature of dermatofibromas which are firm tan papules.

The “dimple sign” is a characteristic clinical feature of dermatofibromas which are firm tan papules.

Solar Lentigines and Ephelides

Solar lentigines are tan or light brown, 1- to 3-cm well-defined macules on sun-exposed areas of older adults, commonly referred to as “liver spots” (Figure 72). They are a marker of sun damage. Ephelides or “freckles” are 2- to 5-mm tan macules on sun-exposed areas that appear in childhood and darken with sun exposure. When solar lentigines or ephelides are larger than 1 cm or irregular in shape, melanoma is in the clinical differential diagnosis and a biopsy should be considered.

Hypertrophic Scars and Keloids

Hypertrophic scars are raised firm nodules or plaques at the site of an injury that can be tender or pruritic (Figure 73). They usually have a good response to intralesional glucocorticoids and may regress spontaneously.

Keloids are firm, rubbery papules, nodules, or plaques that extend beyond the site of injury, but can also form spontaneously, including from inflammatory lesions of acne. They are more common in people with pigmented skin and on the chest and ears. Treatment is difficult and is associated with high rates of recurrence. It requires excision with subsequent intralesional glucocorticoids.

Pyogenic Granulomas

Pyogenic granulomas or lobular capillary hemangiomas are friable red papules that grow quickly and bleed easily (Figure 74). The name is misleading as they are neither pyogenic nor granulomatous. They are more common in women during pregnancy and with certain medications (antiretroviral agents and oral retinoids). Treatment for symptomatic lesions is shave removal or electrocautery.

Epidermal Inclusion Cysts

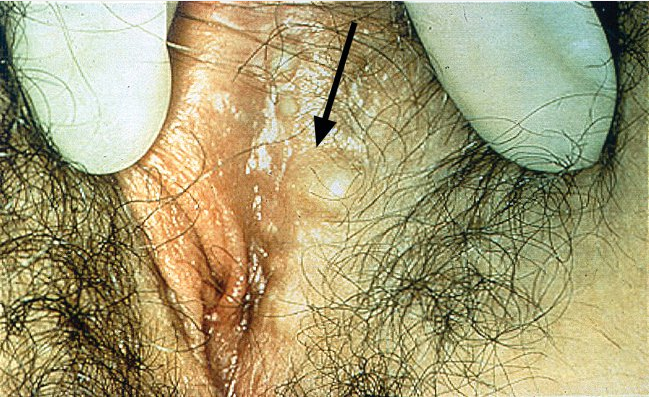

Epidermal inclusion cysts (sebaceous cysts) are subepidermal nodules with an epithelial lining and a core of accumulated keratin debris (Figure 75). They often have a central punctum by which foul-smelling material can be expressed. When epidermal inclusion cysts rupture, they may become tender, inflamed, and occasionally infected. Pilar cysts are similar lesions that occur on the scalp. Treatment is by excision with removal of the entire cyst wall, but the epithelial lining must be removed to avoid recurrences. Incision, as well as incision with drainage, can lead to temporary improvement of an inflamed epidermal cyst; however, recurrences are common as the epithelial lining must be removed for complete treatment. Therefore, these are not the preferred treatment.

Epidermal inclusion cysts are either found incidentally or present as a firm non-tender lump. If they rupture, a local inflammatory response to the necrotic debris released can mimic infection. It is very common for women on the major or minor labia.

Epidermal inclusion cysts are either found incidentally or present as a firm non-tender lump. If they rupture, a local inflammatory response to the necrotic debris released can mimic infection. It is very common for women on the major or minor labia.

Lipomas

Lipomas are benign neoplasms of mature adipocytes that present as mobile, subcutaneous nodules or tumors. Patients can have a single lesion or multiple, and they are most common on the trunk. Angiolipomas are a variant with a vascular component that is often painful and more common on the upper extremities. When symptomatic or larger, lipomas and angiolipomas can be excised.

Digital Myxoid Cysts

Digital myxoid (mucous) cysts are slow-growing, translucent papules most commonly seen in the distal interphalangeal joint or the proximal nail fold of the fingers, although the toes can also be affected. Nail deformity, pain, and discharge can be complications. Symptomatic treatment can be done by incision and drainage, but recurrences are common and there is a risk of infection and scarring.

Xanthoma

Xanthomas are characteristic skin conditions associated with primary or secondary hyperlipidemias. Xanthomas are yellow, orange, reddish, or yellow-brown papules, plaques, or nodules. The type of xanthoma closely correlates with the type of lipoprotein that is elevated. The most common xanthoma types include eruptive, plane, xanthelasma, tuberous, and tendinous.

Eruptive xanthomas present as clusters of erythematous papules typically on the extensor surfaces. They are most often associated with extremely high serum triglyceride levels. Plane xanthomas are yellow-to-red plaques found in skin folds of the neck and trunk. They can be associated with familial dyslipidemias and a variety of hematologic malignancies. Xanthelasma is a type of plane xanthoma localized to the periorbital area, most commonly on the upper medial eyelid (Figure 76), and is characterized by soft, nontender, nonpruritic plaques. Xanthelasma can occur without hyperlipidemia, particularly in older persons, but is often associated with familial dyslipidemias when seen in a younger person. These lesions are a classic feature of primary biliary cirrhosis, a condition often associated with marked hypercholesterolemia. Tendon xanthomas are subcutaneous nodules occurring on the extensor tendons; they are associated with familial hypercholesterolemia.

Neurofibromas

Neurofibromas are benign nerve-sheath tumors that present as soft, skin-colored papules that show invagination of the papule with lateral pressure (“buttonhole” sign). Single lesions are common in adults, especially on the trunk. Multiple neurofibromas are seen in neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen disease) (Figure 77). Treatment of symptomatic lesions is by excisional biopsy.

Precancerous and Cancerous Neoplasms

Skin cancer is a major public health concern, and one in five people in the United States will develop it. Most cases are caused by excessive ultraviolet (UV) light exposure. People of all skin pigmentation can develop skin cancer, but fair skinned persons are more prone to the effects of UV light exposure.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is a malignant neoplasm arising from the basal layer of the epidermis. It is the most common type of skin cancer and cancer in general. Metastasis rarely occurs; however, without treatment, it can cause significant local tissue destruction. Vital structures, such as eyes, ears, and nose, may be damaged. The most common causative factor is UV light exposure. There are different histologic subtypes that result in varying clinical appearance including superficial, pigmented, sclerotic, and nodular. Patients usually present with a new growth that is bleeding or not healing. They often have other signs of photodamage, such as freckles, lentigines, and actinic keratoses.

Nodular basal cell carcinoma is the most common type of BCC. It presents as a pearly or translucent nodule or papule with arborizing telangiectasias. It may have a central depression or ulceration with a rolled waxy border (Figure 78). The term “rodent ulcer” is used to describe the ulceration. Nodular BCC is most commonly found on the face, especially the nose. Histologically, nodular BCC is a low-risk subtype, but its counterpart, micronodular BCCs, poses a higher risk. They can only be distinguished by histologic assessment.

Pearly nodule with arborizing telangiectasias (bottom left) and ulceration characteristic of nodular basal cell carcinoma.

Pearly nodule with arborizing telangiectasias (bottom left) and ulceration characteristic of nodular basal cell carcinoma.

The superficial type of basal cell carcinoma appears as a pink-red patch with or without scale. It may have a slight threadlike pearly rolled border. It can be confused for an actinic keratosis, squamous cell carcinoma in situ, or a patch of dermatitis such as psoriasis or nummular dermatitis. Superficial BCC tends to be a persistent solitary patch that does not respond to topical glucocorticoids. Biopsy provides definitive diagnosis.

Pigmented BCC presents as shiny blue-black papules, nodules, or plaques that can appear translucent with blue-black speckles with a rolled border. It is more common in patients with darker skin.

Sclerotic BCC, which includes morpheaform and infiltrative subtypes, presents as atrophic plaques or papules that can resemble a scar. Although it is the least common, it is a high-risk, aggressive histologic subtype.

The diagnosis of BCC should be confirmed histologically with a shave or punch biopsy. Treatment of BCC should be based on patient's preference and health status, the location of the lesion, histologic subtype, size, and primary versus recurrent nature. Therapeutic options include surgery (standard excision, Mohs micrographic surgery); electrodessication and curettage; cryosurgery; topical chemotherapy; radiation therapy; and for metastatic or inoperable lesions, oral hedgehog pathway inhibitors (vismodegib, sonidegib). Surgical excision is the most commonly used intervention and results in the highest cure rate.

Mohs micrographic surgery is a highly specialized surgical technique that combines pathology and surgery for complete margin control and tissue conservation. It is appropriately used for cancers in the head and neck region, those that are large or recurrent, or in areas where tissue-sparing is critical for function (vital structures) (Figure 79). Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery include tumors with aggressive histologic subtypes (micronodular, morpheaform, infiltrative, perineural involvement), high-risk and cosmetically sensitive locations (face, genitals), large tumors or tumors arising in scar tissue, and in patients who are immunosuppressed. Radiation therapy is generally reserved for inoperable tumors or patients who refuse surgical treatment. Topical chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod can be used for superficial BCC; however, its cure rate is user dependent.

Treatment course lasts for weeks and results in marked inflammation and irritation. Topical therapies are inappropriate for deep, recurrent, or sclerotic tumors. Curettage and electrodessication can be used for superficial or nodular BCCs on the trunk. It should not be used for tumors 2 cm or larger, those with poorly defined borders, recurrent or high-risk histologic subtypes, and those appearing in certain anatomic locations (face, scalp, eyelids). Cryosurgery for BCCs is different than that for actinic keratosis. The margin, depth, and temperature have to be monitored to achieve cure.

Follow-up skin examination every 6 to 12 months is recommended as the risk of developing another BCC is increased. Prevention with sun protection is highly recommended including routine use of sunscreens with sun protection factor greater than 35, protective clothing (wide brim hats, long sleeves), and avoidance of midday sun (10 AM to 2 PM).

Actinic Keratosis

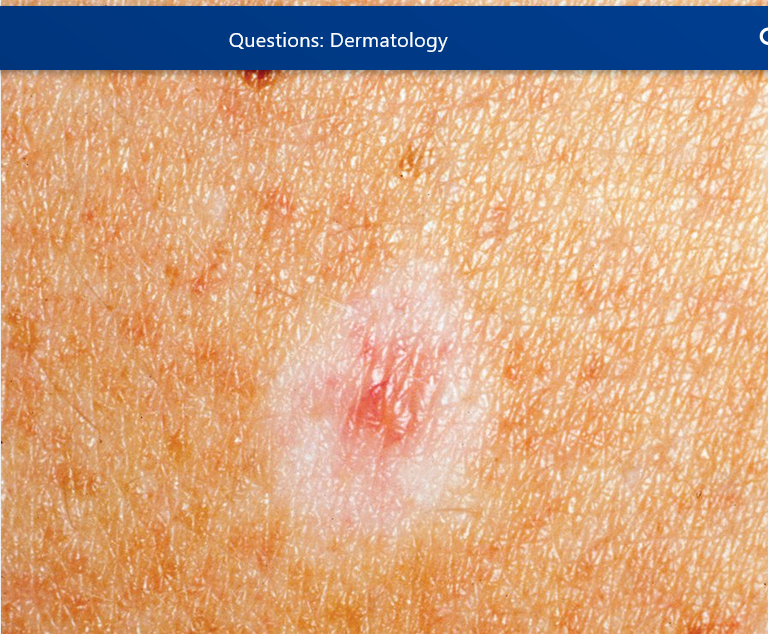

Actinic keratoses are precancerous lesions of the epidermis. Approximately 1% to 5% of actinic keratoses will develop into squamous cell skin cancers. They present as ill-defined pink scaly (“sandpaper”) thin papules or plaques mostly in sun-exposed areas (Figure 80). Individual lesions can be treated with cryotherapy. In patients with diffuse actinic damage, field treatment with topical chemotherapy creams (such as 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod) or photodynamic therapy can be used. Lesions that do not resolve with cryotherapy or are more indurated will require a biopsy to rule out an invasive neoplasm.

Actinic keratoses are typically pink thin papules that occur on sun-exposed areas, particularly the face and dorsal arms. Actinic keratoses result from chronic sun exposure, and their presence identifies persons who are at increased risk of developing invasive squamous cell carcinomas. Actinic keratoses are a precancerous condition.

Actinic keratoses are typically pink thin papules that occur on sun-exposed areas, particularly the face and dorsal arms. Actinic keratoses result from chronic sun exposure, and their presence identifies persons who are at increased risk of developing invasive squamous cell carcinomas. Actinic keratoses are a precancerous condition.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), the second most common skin cancer, is a malignant neoplasm of keratinocytes. It presents as pink, scaly indurated plaques, papules, or nodules that can ulcerate, bleed, or become crusty (Figure 81 and Figure 82). It can be painful. Risk factors are UV light, ionizing radiation, chemical carcinogens (coal tar, soot, and arsenic), viruses (human papillomavirus), and immunosuppression (organ transplant, hematologic malignancies, HIV infection). SCC occurs in areas of sun exposure and areas of chronic injury (burn scars, irradiated sites, erosive discoid lupus erythematosus). In comparison to lightly pigmented patients, those patients with darker pigment more often develop SCC in regions with chronic inflammation or scarring and more frequently on the lower extremities. SCC can be locally invasive and has the potential to metastasize. Histologically, it can range from well-differentiated SCC to poorly differentiated SCC, which is the more aggressive subtype. High-risk factors for SCC are tumor diameter greater than 2 cm, tumor thickness greater than 2 mm, poorly differentiated subtypes, perineural invasion, and tumor location of the ear or nonglabrous lip (Figure 83).

Pink scaly plaque consistent with squamous cell carcinoma.

Pink scaly plaque consistent with squamous cell carcinoma.

Pink hyperkeratotic nodule on sun exposed skin consistent with squamous cell carcinoma.

Pink hyperkeratotic nodule on sun exposed skin consistent with squamous cell carcinoma.

Squamous cell carcinoma lesions on the lower lip most commonly arise from sun damage, often in the setting of actinic cheilitis.

Squamous cell carcinoma lesions on the lower lip most commonly arise from sun damage, often in the setting of actinic cheilitis.

With SCC in situ (Bowen disease), malignant keratinocytes are confined to the epidermis. It appears as larger scaly pink and tan plaques with well-defined borders (Figure 84). Skin biopsy can distinguish SCC in situ from actinic keratoses.

Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ) typically presents as a gradually enlarging, well-demarcated erythematous plaque with an irregular border and surface crusting or scaling.

Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ) typically presents as a gradually enlarging, well-demarcated erythematous plaque with an irregular border and surface crusting or scaling.

Surgical excision including Mohs micrographic surgery for high-risk SCC tends to be the first-line treatment given its potentially aggressive behavior and risk of metastasis. Radiation is an option if surgery is contraindicated. In cases of metastasis, chemotherapy can also be considered.

Keratoacanthoma

Keratoacanthoma is considered to be a variant of SCC by some and a benign tumor by others. Histologically, it can resemble an SCC. It has a distinct appearance and clinical course. It appears rapidly (within 4 to 6 weeks) as a round pink nodule with a central, keratin-filled crater, giving it a “volcaniform” appearance (Figure 85). After its rapid growth, some keratoacanthomas tend to involute in 6 months. Because it is difficult to differentiate from SCC, they are often treated with surgical excision.

Rapidly growing, pink “volcaniform” nodule with central crust that is characteristic of a keratoacanthoma.

Rapidly growing, pink “volcaniform” nodule with central crust that is characteristic of a keratoacanthoma.

Malignant Melanoma

Melanoma is a malignant neoplasm of the melanocytes. Although it is less common than BCC and SCC, it is histologically aggressive and has a much higher rate of metastasis. It is responsible for most skin cancer deaths. In the United States, the incidence of melanoma is increasing faster than any other cancer. The estimated lifetime risk of developing melanoma is 1 in 50. It tends to affect a younger population. There are four clinical subtypes: superficial spreading, lentigo maligna, acral lentiginous, and nodular melanoma. Risk factors include UV light (both chronic and intermittent blistering sunburns), genetics (family history, and CDKN2A and CDK4 gene mutations), large number of nevi, dysplastic nevi, and fair skin.

In general, the ABCDEs of identifying characteristics can help diagnose melanoma where “A” stands for Asymmetry, “B” for irregular Border, “C” for multiple Colors, “D” for Diameter greater than 6 mm, and “E” for Evolution or change over time. Not all melanomas follow all of these characteristics, so if there is a lesion that is different from the patient's other nevi, a biopsy should be considered.

Superficial spreading melanoma is the most common type (Figure 86). It can occur anywhere on the body; however, in men, the most common location is the back, whereas in women, it is more often found on the legs.

Lentigo maligna is more often found on the head and neck region. It is associated with frequent chronic UV light exposure. It is usually found in older patients, peaking in the seventh and eighth decades of life. It presents as ill-defined, asymmetric brown or black macules or patches, often reaching a diameter of 5 to 7 cm prior to invasion (Figure 87). The change and darkening of the lesion can be very insidious and can be mistaken for a solar lentigo or seborrheic keratoses.

Acral lentiginous melanoma occurs on the palms, soles, and distal fingers and toes. It is an ill-defined, black macule plaque, and it more frequently occurs in patients with darker skin (Figure 88). The average time to diagnosis is 2 years. The 5-year survival rate for melanoma in blacks and Hispanics, even after adjusting for age, stage, site, and socioeconomic status, is lower compared with white patients.

Nodular melanoma begins in the vertical growth phase and is more aggressive. It is rapid growing and presents as blue-black, smooth, or eroded nodules occurring anywhere on the body (Figure 89).

All suspicious pigmented lesions must be biopsied. The preferred method to biopsy a pigmented lesion is an excisional biopsy with 1- to 2-mm margin to obtain the entire lesion and to prevent sampling error. Shave biopsies should be avoided in most pigmented lesions as there is risk of transecting a melanoma and preventing true staging of the lesion. A modified technique that can be helpful is the “scoop” biopsy where the deep dermis or subcutaneous tissue is removed to get underneath the lesion. In wide, ill-defined lesions, it may be prohibitive to remove the entire lesion, so an incisional biopsy is acceptable. Definitive treatment cannot be determined until histologic confirmation and final staging of the tumor is completed.

Poor prognostic factors include male gender, increasing age, increased tumor thickness (Breslow depth), ulceration, increased tumor mitotic rate, and head/neck/trunk locations. Melanomas are staged with the tumor, nodal, and metastasis (TNM) system (https://cancerstaging.org/references-tools/quickreferences/Documents/MelanomaLarge.pdf).

Survival is dependent on early diagnosis. Treatment is based on the stage of melanoma. In the first and second stage, surgical treatment is used to remove the lesion and a margin of clinically normal skin (wide local excision). The size of the margin is based on the depth of the lesion. Melanomas that are stage IB or higher are often considered for sentinel node biopsy for assessing prognosis. Stage III melanoma is treated with wide local excision, lymph node dissection, and possible adjuvant interferon. Immunotherapy has emerged as the primary systemic treatment for stage IV melanoma. Combination treatment with an anti-PD1 antibody (pembrolizumab, nivolumab) with ipilimumab, an anti-CTLA4 antibody, is most often selected for patients with metastatic melanoma (see MKSAP 18 Hematology and Oncology). Survival data suggest that up to 80% of patients receiving this combination will be alive at 2 years. Chemotherapy is typically reserved for patients who have progressed despite optimal systemic therapy. Radiation is usually reserved for palliative therapy for metastasis to the brain and bones. Thorough follow up including a full-body skin examination at routine intervals is crucial for patients with a history of melanoma.